Spoilers ahead for the entire novel. There are brief mentions of being outed against one’s will and a sexual abuse plotline.

Casey McQuiston’s 2019 novel Red, White & Royal Blue is obviously not meant to be a serious commentary on the current political state of affairs in the U.S.A. It is over-the-top outlandish wish-fulfillment for a person of a certain political stripe. If you are not super-duper lefty, this book is decidedly not for you, and you’ve probably given it a pass.

I am super-duper lefty, but the only reason I mention this is that while I’m not American, which understandably makes this book less “for me,” this book is intended to speak to people like me, who think the way I do about certain social issues. I’m not going to hate on it because it assumes everyone reading shares its leftist and progressive ideals. At the same time, I feel weirdly curmudgeonly being critical of it in any way as it is so unabashedly a fantasy. Any dislike of its candy-coloured utopian alternate timeline is, arguably, beside the point, as this is a romance, not a realistic political drama.

I’ll give you a taste of the book’s flavour with a bit of a summary which goes on too long because it’s rather fun to summarize. This novel starts with Henry, Prince of Wales, and Alex, the son of the American President, who hate each other for no good reason, getting into a tiff at a royal wedding of the prince’s brother. Of course, they wind up somehow falling into the very expensive royal wedding cake, Alex hauling down Henry until they land in a pile of icing sugar and wasted taxpayer dollars. It continues with the two of them being forced into a “no, we’re really best friends, not mortal enemies” joint PR tour of the UK, in which they appear on morning shows and make sure to arrange a photocall afterwards. During these plot machinations, while visiting sick children in the hospital, the Prince and the FSOTUS escape a (false) gun threat by being shoved into a hospital broom closet, a gesture whose symbolism is not lost on either character.

However, before they can get together, Alex must first realize he’s bisexual, after Prince Henry confesses to his crush on Alex, then kisses him during a party. Alex finally figures out why he is so into the idea of that, having never set aside the time to consider his sexuality before – a part of the novel I loved. Chapters later, having both definitively exited that literal and metaphorical closet, they are kissing wildly against a portrait of Alexander Hamilton in the White House. The couple’s secret relationship develops during night out at the karaoke bar, which Alex and Henry attend with their best friends and favourite siblings. Everyone wears matching silk kimonos with customized embroidery featuring cheeky names for each member of the group. The narrative gaze lingers on happy montages of beautiful, successful queer British and American millennial/gen-Zers photogenically flirting with each other and having a grand, carefree time, not worried about a pandemic, paying their rents, civil rights protests or domestic terrorists attacking those civil rights protestors. Henry, who is rather shy, drinks enough liquid courage to belt out “Don’t Stop Me Now” at the mic. Alex, not shy at all, hauls him off to the bathroom for some private fun as a reward.

The book contains a scene where Alex storms over to Buckingham Palace after purchasing a first-class plane ticket on his own dime, after being ghosted by Henry, who can’t deal with Alex’s overtures towards commitment. Given his role as the spare to the throne, Henry’s life is supposed to involve churning out heterosexual babies with a nice member of the nobility. This would preclude a relationship with Alex, whom he never expected to seriously like him enough for that kind of commitment. Alex, despite being on the “do not admit” blacklist post-breakup, negotiates his way into the princely apartments with the help of a savvy security staffer with an inside connection: her fiancé is on Henry’s security detail. Once he’s busted past the guards, Alex declares his undying love for Prince Henry and throws himself at his feet. Of course, it works, because this book’s sensibility is firmly in Hollywood, not the territory of a British rom-com. According to its logic, since Henry is a classically English repressed sort of man, his tender heart wants nothing more than an American grand gesture of affection. And it got me, it really did; I mean, all these concocted scenes, which are not trying to be anything but indulgent fun and are certainly a distraction from pandemics, civil rights protests and domestic terrorism. How can a person of a certain political stripe possibly dislike a single thing about a story like that? What kind of pitiless, mean-spirited monster would one be to do so?

More than this, how can anyone hate the book’s treacly ambitions? Because that is what it aspiring to be: a confection, and one concocted by a very masterful pastry chef at that, whose every writing decision seems so clever and deliberate it cannot be doubted that if this wanted to be some other sort of book about an intercontinental political love-affair, you’d be reading that instead, and it WOULD still be an NYT bestseller. This is a story about optimism in politics, as much as it is about a romantic relationship. It is a moral fable in which hard work is rewarded, politicians possess virtue alongside hustle, and the public can be trusted to make the right decision on both presidential elections and whether they should celebrate high-profile gay relationships between the children of heads of state (and ceremonial figureheads). It’s a book in which a politician’s private email server leaks are honestly no big deal and have no effect on the upcoming election. The politician who leaks a rival’s emails in response to the initial hacking is not motivated by pure greed and selfishness. He wants to achieve a greater political good by bringing down a corrupt candidate who sexually abused and tried to blackmail him, possibly sacrificing his own career in the process.

It is also a book in which un-politically correct opinions, like the ones voiced by a WASPy Dem staffer, that certain red states are too far-gone to be worth courting by the Democrats; or the opinions voiced by the highly fictionalized queen of England, that the majority of the public will not support gay rights now or ever, are definitively trounced and proven wrong. This feels a bit like grandstanding a position on the right side of history, as much as I agree with those sentiments. At the novel’s conclusion, the left wins the political and the culture war. There is kissing and celebration. History is made: a tagline of the lover’s hacked emails, in which Alex compares his relationship with Henry to other famous historical gay love-affairs, is enshrined on a popular T-shirt, with the slogan, “History, huh?” Everyone waves around their pansexual-flag-embroidered jean-jackets in glee and no one is murdered while they are out peacefully protesting.

So why do I feel so let-down and bitter by that aspect of the book, as though I have just binged a box of chocolates and been left with a tremendous sugar headache? Because, damn, at certain points, this was some of the best sugary chocolate I have ever eaten, so it was definitely worth it, but we’ll return to that later. Why does presenting common decency and morality in a context that is deliberately fantastical and purely leftist seem so disheartening? Why do I feel such disappointment that most of the side characters – the women president, the hero’s sister, and his best friend – three women who are brilliant at their jobs and endlessly supportive of the hero, seem like little more than author mouthpieces for clever wisecracks and correct decisions that fall on the right side of history, and not actual people? Why does it frustrate me so much that these women can do no wrong and make not a single mistake, as though they might be less worthy of rooting for if they dared to be imperfect?

The tacit assumption of the book is that the entire political process of elections in the States, a bloated and yearslong endeavour that consumes billions of dollars and results in a dysfunctional political system that can’t manage to return people’s money to public benefits, is intrinsically right and good. The election swallows an entire year of White House political energy in this novel. It is the first thought on Alex’s mind at every moment when he’s not thinking of his love for Henry or his future career. Domestic politics aren’t mentioned once, and no one seems to have a problem with that. I mean, if you are this invested in the system, of course, you want that personal and organizational cost to pay off with success because otherwise, it is a colossal waste of resources. Slow blink; stare off into the distance, sigh.

I listen to Pod Save America more often than I have any business doing as a non-national. From the perspective of political organizers, I know that this kind of investment of time and money is simply what American politics demands in its current form. One cannot even reshape that system without being immersed within it, paying the price and accepting the cost at every level of meaning for that term, so it’s not as though I’m unsympathetic to the realities of being a politician in the USA. It’s not as though I literally want this novel to be about the USA completely overhauling its political system to become Sweden, as that would be beyond the scope of any novel where politics are not at the very center of things. But even so, the limits of this novel’s idealism made me shake my head at actual problems too great to be handwaved away in an escapist flight of fancy. Just as normalized as the accepted path to political success is the idea, in this book, that the first son and daughter of the president naturally become celebrities and nepotistically fill public roles within the administration. This is a reality that has garnered no small amount of critique for a family on the other side of the political aisle. I think such nepotism is wrong in any circumstance, for the record. But is it even fair to be upset that the imagination of this book doesn’t extend far enough to question certain assumptions about the ideal political outcome? Is it too much to demand of a work of fiction which does not pretend, for a moment, to be real, or that its goal is anything other than a “deserving heroes” AU within an existing political framework?

Even so, are the heroes entirely deserving? How do we hear so much about Alex wanting to help people by being a politician, but are given zero examples of him actually helping people through political action, for instance? Alex doesn’t HAVE to go have some manufactured encounter where he helps a troubled youth through a government-sponsored outreach program, or something, just to convince me, Ms. Canadian Crankpyants without a dog in this fight, that he’s a good person and not just in the political game for the sake of his vanity, as I would argue he seems to be on occasion. At the conclusion of the novel, Alex’s sister June sells a memoir to a publisher. Does a mid-twenties daughter of a politician really have enough life experience to merit writing a memoir, and is it fair that the memoir is primarily going to be read by people interested in her mom’s politics, and does celebrating this not seem to cheerfully reinforce our present reality where power, wealth and privilege simply beget more generational power, wealth and privilege and opportunities for personal advancement?

You get the idea. My critique boils down to, “Instead of becoming pure escapist fantasy, the specific ways in which the book’s political plot is congruent and incongruent with reality dragged me down.” Which is quite personal, and certainly not a widely shared opinion, as many people adored this book’s political escapism. The author, in the postscript, has indicated that this is how they wanted to serve the people who are working so hard in public service: by giving them a fantastical alternate world to mitigate the sting of the present one, the sort of world they’d want to live in themselves. This is arguably an act of humility, not hubris, creating a better imaginary world to soothe those people for whom reality is presently an unbearable burden. “It’s just not for you,” you might rightly say, and I cannot disagree.

But parts of this novel are SO very much for me that it isn’t accurate to say it simply wasn’t for me. The letters the guys exchange, for example – Oh God, the letters are everything. The newspaper and groupchat epistolary elements were not Canquilt’s favourite in her Drag Your Favorites review, though she did enjoy the emails, so your mileage may vary. I just love the feeling that we’re peering over someone’s shoulder when letters are included; that we’re reading about the protagonists’ heart’s desires, their secret selves they keep hidden from the world and only revealed to the person they love most. This novel’s third act sees the pair of young lovers breathlessly exchanging over-the-top romantic emails footnoted with historical quotations from real gay love affairs. In these letters, when they aren’t flexing their knowledge of, for example, composers of the Romantic movement, as they are wont do in person, they explain their affection for each other through invented fairytales and landscape allegories. There seems to be no metaphor bold enough to convey their passions. Alex writes to Henry: “On the map of you, my fingers can always find the green hills, wales, cool waters and a shore of white chalk. The ancient part of you carved out of stone in a prayerful circle, sacrosanct. Your spine’s a ridge I’d die climbing.” (447) Now I’m sighing and staring off into the distance for quite different reasons.

A frequently mentioned critique of this book is that it has a tendency towards try-hard-ness with its quippy cleverness. I mean, here is how Alex’s best friend Nora describes her outfit for one event:

“i’m going for, like, depressed lesbian poet who met a hot yoga instructor at a speakeasy who got her super into meditation and pottery, and now she’s starting a new life as a high-powered businesswoman selling her own line of hand-thrown fruit bowls.” (212)

Yeesh. The conversations often have this air of people showing off for each other, used to perennially auditioning their smarts for an audience, almost anticipating their screencaps are going to get posted to a subreddit or popular Instagram page. This book has no chill in that regard. Someone’s almost always being impossibly, performatively clever to someone else. Says the President, after the Alex-and-Henry falling into the cake scandal: “As your mother, I can appreciate that maybe this isn’t your fault, but as the president, all I want is to have the CIA fake your death and ride the dead-kid sympathy into a second term.” (37)

Yet in the epistolary portion of the narrative, that over-the-top effort just works. Where the tone could be snarky before, here it is unabashedly earnest and tender. Besides, love-letters are supposed to be a combination of try-hard and earnest, in which you know the other party will not judge you for your indulgences, for your craziest hyperbole and your wildest flights of fancy, because they are so madly in love they’ll forgive anything. The love letters in the novel become a layer cake with another layer cake on top and extra maraschino cherries drowned in heaps of whipped cream, and I wanted to drown myself in them, reveling in vicarious happiness all the way down.

“I thought, this is the most incredible thing I have ever seen [meaning seeing Alex for the first time]” writes Henry, of the moment he fell in love with Alex – at first sight, of course, when they were both teenagers. “And I had better keep it a safe distance away from me. I thought, if someone like that ever loved me, it would set me on fire. And then I was a careless fool, and I fell in love with you anyway.” (300)

Says Alex, describing his love for Henry after having a bit too much whiskey:

“there’s a corner of your mouth, and a place that it goes. Pinched and worried like you’re afraid you’re forgetting something. I used to hate it. used to think it was your little tic of disapproval. but I’ve kissed your mouth, that corner, that place it goes, so many times now. I’ve memorized it. topography on the map of you, a world I’m still charting. I know it. I added it to the key, here: inches to miles. I can multiply it out, read your latitude and longitude, recite your coordinates like la rosaria.” (319)

In the tradition of sixteenth-century explorers charting the new world, and maybe a bit of winking reverse imperialism for the country that gave America its language and staked its own claim there, Alex tells Henry that the topography of his body is as sacred to him as the key he wears next to his heart, the key to his family home. He’s saying that he holds this quirk of Henry’s physical self, that twitch of his mouth, that once meant one thing to him and is now revealed to be quite another expression of sentiment, as a token of that private persona only a lover knows. He has memorized it with all the fervour of religious prayer, recalling the metrics of Henry’s body as though he can summon him back, translate him over this impossible physical and cultural distance that separates them. It’s so beautiful and thoughtful. I have rarely read another romance novel in which the vulnerable passion of first love is so fearlessly written. For that alone, the entire book is worth it. Those are the scenes to which I’ll be returning when I reread it. Because yes, as much as the political assumptions bothered me, the love story was that wonderful.

On that try-hard-ness I mentioned earlier, though…Here I am, utterly a hypocrite, because I am someone who writes three thousand words over-intellectualizing erotica and now some weirdly personal, nitpicky hit piece on a gay prince/American royalty escapist fantasy. And shouldn’t we be celebrating a writer who takes such pains to make everything in her fluffy, cotton-candy-book bright and sparkling and shiny, as clever as can be, and as thoughtful as is humanly possible, who admits in her acknowledgments that she pruned 40,000 words from the draft at one point and cites her genuinely impressive research into gay history archives?

But there is nothing about this book that is not striving for something, striving for the perfect one-liner, or the perfect post-collegiate path to success for a first daughter with writerly aspirations, or the perfect near-miss yet plausible-recovery re-election story for the incumbent president. It even attempts to mitigate some of the darker territory the book skims over by, well, this sort of lampshade hanging, in which it’s acknowledged that things historically have been awful but, y’know, not above poking fun at:

“Listen,” Alex tells her [his sister June, before the royal wedding commences] “royal weddings are trash, the princes who have royal weddings are trash, the imperialism that allows princes to exist at all is trash. It’s trash turtles all the way down.”

“Is this your TED Talk?” June asks. “You do realize America is genocidal empire too, right?” (20)

Genocidal empire lol let’s go try on some totally edgy bomber jacket for Mom’s big political moment and never mention colonialism again! I mean…I understand not wanting to make a romance book about reckoning with the actual legacy of genocidal empires, but I do question whether being quite so blasé about things that are terrible isn’t a bit too flippant.

McQuiston goes heavy on a Protestant qua late-capitalist idea of virtue through perpetual hustle, in which it’s praiseworthy to sleep at your desk and drink to cope with your stress and postpone any self-reflection about your sexual identity that might be painful because who even has the time for that (a portion of the novel I found frighteningly relatable, for the record) and to eat junk food for dinner and have a nervous breakdown the moment you stop spinning in the endless toil of to-do-lists and career ladder climbing. It all becomes more than a little exhausting, even for purportedly escapist fun. Interesting, isn’t it, that work-life balance has no part in the fantasy of the ideal political landscape, that every single character is a nose-to-the-grindstone hustler who won’t quit and has no idea what to do with themselves when their workload is diminished. Alex, when he’s fired from his mom’s campaign as a political liability once his love-affair is outed, basically goes on long runs, freaks out a lot, and lets angst spur him to take the LSAT, lest we think, for a single minute, that he’s some kind of lazy fuck-up for not maximizing his downtime. That might make him…a bad person!

I don’t want this to just be one long bitch-session about how certain parts of the book didn’t work for me sandwiched around an enthusiastic rave for the portion that did. And really, McQuiston is so funny and clever and thoughtful in her work that I am certainly interested in whatever she does next. I am fairly confident the problems I have with this specific novel would be almost impossible to replicate in any other context and I’ll probably love her next one.

But I think what was missing, for me personally, was this idea of the worthwhile struggle, of really suffering for a cause that is worth it. Don’t get me wrong – both Alex and Henry DO suffer for their identity, and the cost of being honest means having their names and their relationship dragged through the press after it is outed against their wills, which is a legitimately terrifying prospect. And the idea that gay people need to be shown as suffering for who they are is a tired one; completely overdone. We don’t need more fictional gay suffering whatsoever. But I think we do need an aspirational world in which the everyday imperfections of others and ourselves – when people voice ideas we don’t agree with, when we undertake the occasional selfish action we have not considered fully enough, when we may fail to succeed – are accommodated in a visionary ideal reality, a place where goodness and morality are apolitical. Where politics are other than press optics; where meaning is found beyond PR appearances, where failure to achieve a goal is a more profound teacher than success. I would like an ideal escapist world to seem not quite so impossible to imagine as real, because it is populated by imperfect people who resemble ourselves, who we root for to succeed, and who we still have sympathy for when they don’t. Even in a romance novel. Especially for these two lead characters, who felt so real to me except for their unreal, idealized world.

All that said, this is a decade-defining novel, and we’re going to be talking about it for years to come. You should definitely read it, and you should definitely rave to me about how much you loved it if you did. If there’s one thing I love, it’s when people love something so much that they persuade me to change my mind and fall in love with it; to see that smirky humour in a way I’ve never considered before, until I’m writing love-letters to it myself.

This essay was previously published on Reddit.

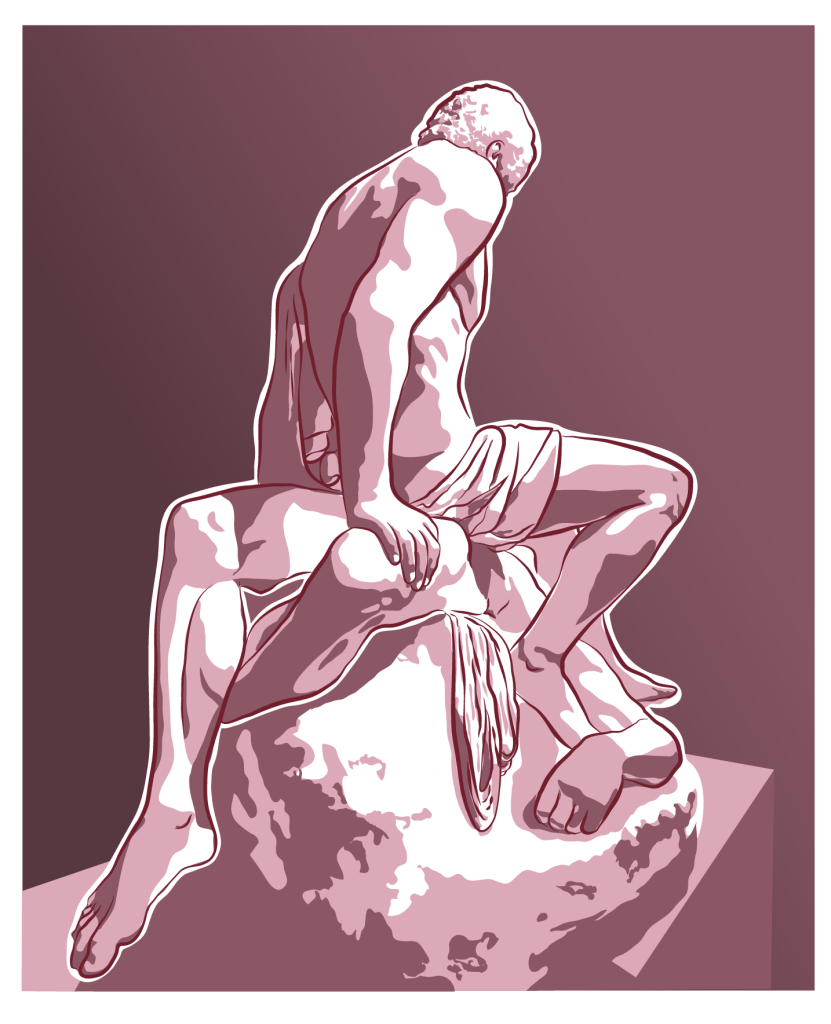

Art based on Canova’s Theseus and the Minotaur, drawn by Eros Bittersweet, 2023

Leave a comment